The Edit That Will Live in Infamy

The Edit That Will Live in Infamy

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, at the podium; Vice President Henry Wallace, left, and Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn on the dais; Captain James Roosevelt, far right, Joint Session of Congress, December 8, 1941.

From The National Archives:

Early in the afternoon of December 7, 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his chief foreign policy aide, Harry Hopkins, were interrupted by a telephone call from Secretary of War Henry Stimson and told that the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor. At about 5:00 p.m., following meetings with his military advisers, the President calmly and decisively dictated to his secretary, Grace Tully, a request to Congress for a declaration of war. He had composed the speech in his head after deciding on a brief, uncomplicated appeal to the people of the United States rather than a thorough recitation of Japanese perfidies, as Secretary of State Cordell Hull had urged.

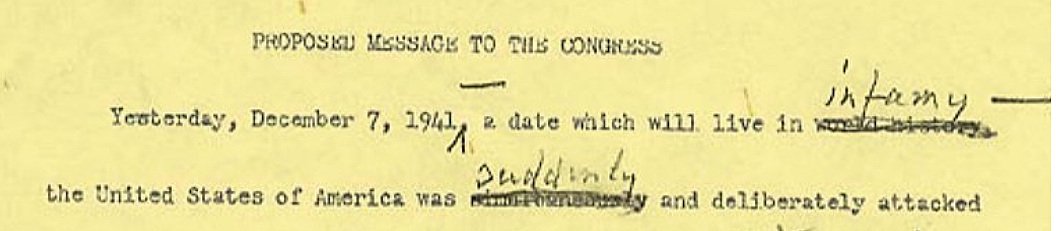

President Roosevelt then revised the typed draft—marking it up, updating military information, and selecting alternative wordings that strengthened the tone of the speech. He made the most significant change in the critical first line.

Imagine FDR running his pencil over the line and stopping at the words “world history.”

Without question, the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor would go down in the history books. But would those words capture the context of the act—conducted while the United States was “still in conversation” with the Empire of Japan, looking to maintain peace in the Pacific? Would they have communicated the nature of the attack—deceptive, deliberate, sudden, brutal, heinous?

That is the kind of question a skilled copy editor will ask. If the answer is no, the editor will search for a better word or two, preferably one. Roosevelt found the right word—infamy—and his powerful address has gone down in world history as “The Infamy Speech.”

It’s also worth noting FDR’s use of the word “date” versus “day” in his opening phrase. He chose “date” deliberately. According to the editors of Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary of Allusions .and American Ethnologist, whose work is cited in Wikipedia, “the speech's infamy line is often misquoted as ‘a day that will live in infamy’. However, Roosevelt emphasized the date—December 7, 1941—rather than the day of the attack, a Sunday … He sought to emphasize the historic nature of the events at Pearl Harbor, implicitly urging the American people never to forget the attack and memorialize its date.”

A finicky copy editor might quibble over FDR’s choice of “which” versus “that,” but, under the circumstances, it’s unlikely the president was worrying about restrictive versus nonrestrictive clauses.

Listen to the speech as FDR delivered it live to Congress and to the largest audience in American radio history, with nearly 82 percent of the people tuning in.